The $: Their currency – our problem

As Ben Bernanke’s mandate as chairman of the Federal Reserve (the “Fed”) ends, it is time to assess the impact that the American central bank has on the world economy. The US enjoys what former French president Valéry Giscard d’Estaing once called “the exorbitant privilege of the dollar”, which is the de facto reserve currency of the world. An advantage for the US, allowing it to run large current account deficits and pay little interest on its debt without worrying about a balance of payment crisis. A disadvantage for the rest of the world, since decisions made by the Fed have direct and indirect consequences on their economies.

A tale of unconventional policies

Since 2008, most developed economies central banks have responded to the crisis with unconventional monetary policies. These policies were aimed at pushing interest rates as low as possible in order to fight deflation. These mainly include zero-interest rate policy and quantitative easing; that is when a central bank buys government bonds or mortgage-backed securities from private banks or institutions in order to push yields down on those financial assets and thus increasing the monetary base and its balance sheet.

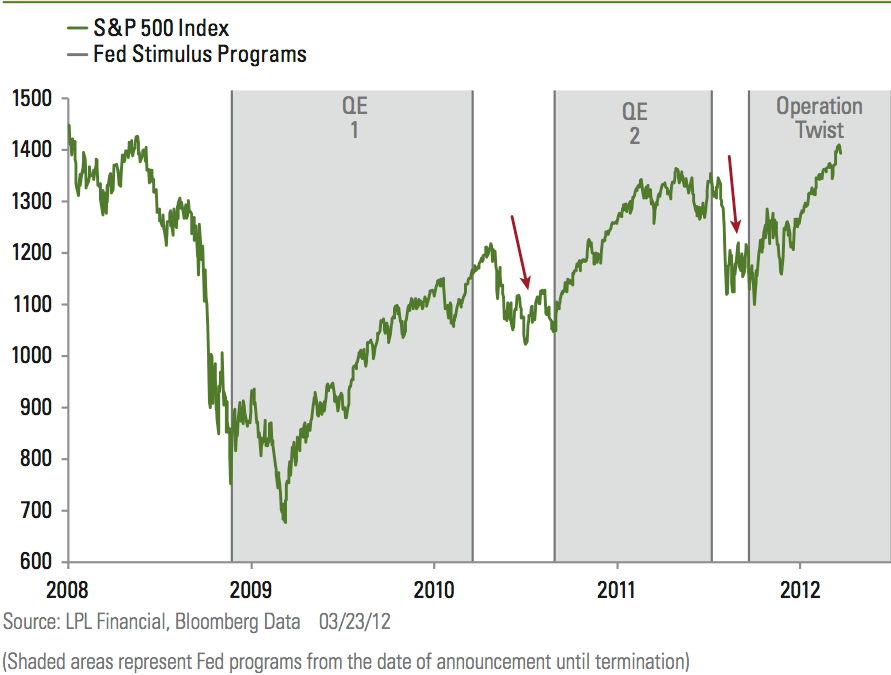

While QE1 helped the US economy get out of the recession, the effectiveness of QE2 and now QE3 are put into question. In QE3, also infamously called QE-infinity, the FED buys $85 billion per month of bonds. It’s almost a new deal every month that is being injected into the economy. To put it into perspective, Franklin Roosevelt’s new deal was around $100 billion in today’s dollars.

These policies are aimed at fighting unemployment, deflation and helping a fragile housing market, but they have increased income inequality, caused asset class inflation and recently disrupted emerging market economies. Worse, they have made financial markets addicted to easy money and might even have sowed the seeds of the next crisis.

Some blame the “Greenspan Put”, the monetary approach of former FED chairman Alan Greenspan, and his decision to keep interest rates low in the period 2001-2005 for the financial crisis of 2008. At the height of 2008 crisis, President George W. Bush famously said in a press conference: “Wall Street got drunk”. But if Wall Street got drunk, who poured the liquor? William M. Martin, FED chairman 1951-1970, once said that the job of the Federal Reserve is “to take away the punch bowl just as the party gets going”. Failing to do so can have dire consequences on the world economy and financial markets as we have experienced in 2008.

Last summer the Federal Reserve announced that it would start the process of what it calls tapering which is a gradual reduction in its purchases of bonds. A signal that it is starting its exit strategy from unconventional monetary policy due to improvements in US jobs numbers and a recovering US economy. Although Wall Street has recovered, Main Street is still lagging behind and the labor participation rate has declined while it remains constant in the Euro zone. If US labor participation rates were at 2010 levels , US unemployment would have easily reached 11.5% today. This huge fall in labor participation rates can not only be explained by people retiring but by discouraged young Americans not entering the workforce and long-term unemployed people leaving it.

While the effectiveness of QE on the real economy and on unemployment is a matter of debate, its effect on the stock market, income inequality and housing is not. Andrew Huszar, a former Fed official who was responsible for the program apologized to America in a WSJ opinion article titled : “Confessions of a Quantitative Easer”. According to him: “We went on a bond-buying spree that was supposed to help Main Street. Instead, it was a feast for Wall Street.” He thinks the FED should have stopped after QE1. Quantitative Easing might well be one of the largest transfer of wealth to the top in history, by artificially boosting the value of financial assets the Fed is subsidizing -(un)intentionally- the rich.

From BRICS to Fragile Five

The acronym BRIC stands for the four highest developing economies (Brazil, Russia, India, China and later joined by South-Africa). It was first introduced by Jim O’Neill, retired chairman of Goldman Sachs Assset Management, in a 2001 paper titled “Building Better Global Economic BRICs”. Today it is very clear that the only letter that really matters in BRICS is C, for China.

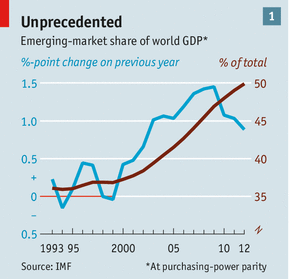

The tapering announcement caused large capital outflows of emerging markets. Just this month there have been capital outflows of just over $12 billion. Recently, Morgan Stanley named the Indian rupee, Indonesian rupiah, Brazilian real, South African rand and the Turkish lira as the “Fragile Five”. Since tapering was announced, the real and rupee lost 15%, the Turkish lira and Indonesian rupiah lost respectively 21% and 24% against the US dollar. It looks like the 1997 Asian financial crisis, that raised fears of an economic meltdown, all over again. But this time worse, because emerging markets total share of world GDP in 1997 was about 35%, today it’s 50%. A slowdown or boom in growth rates of emerging markets has a larger impact on global GDP growth today than it ever did before. Yet as political scientist Ian Bremmer pointed, a China growing at 7.5% today has a bigger impact on global growth than a China growing at 11 or double digit growth numbers 8 years ago. Because their global share of GDP has become larger and so did the global GDP pie.

From The Economist article : “When Giants slow down”

The FED has a dual mandate giving to them by Congress : 1. maximum employment, 2. price stability while the ECB only has the latter one. The health of emerging market economies does not fit into that equation and rightly so. The FED is the central bank of the US not of the world, although it has shown flexibility when it has secretively bailed out European banks through the ECB by using currency swap arrangements that are technically not loans (which the Fed is prohibited from doing to give foreign banks).

The Euro an alternative to the dollar?

The dollar will retain its exorbitant privilege for the foreseeable future, but the world shouldn’t be satisfied with this situation. The October debt-ceiling showdown on Capitol Hill proves that the world’s economic condition cannot solely depend on the political squabbling of one nation. Let’s face it, the US keeping its privilege isn’t because of fiscal discipline nor good economic fundamentals, it’s because the US dollar is the best looking horse in the glue factory. When you ask American policymakers if they’re worried about China or foreign investors selling their dollar denominated assets or bonds, they’ll likely tell you “if not the dollar what else? the euro ? give me a break!”.

The euro as a currency has an excellent track record when it comes down to price stability, but it lacks the most essential part, a government and treasury to back it. A very interesting aspect of the eurozone crisis was the relative strength of the euro. But this was merely due to a weakening dollar rather than good economic fundamentals in the Euro area. The eurozone crisis wasn’t a currency crisis, it was a sovereign debt and balance sheet crisis but above all a crisis of European governance and crisis management. Greek GDP share of total European GDP was less than 3 %, yet it put the whole eurozone’s viability into question. While almost bankrupt California with a GDP accounting for almost 14% of the US economy didn’t even put into question the legitimacy of the US dollar.

Yet Europe has a lot of assets if it wants to dethrone the dollar: the euro already accounts for 25% of global foreign exchange reserves something unimaginable back in the 90’s, Europe’s economy is the largest on earth, the Euro area and EU have a trade surplus with most international partners and a shrinking trade deficits with China, Japan and Russia. The Chinese renminbi is not fully convertible which makes it an unlikely pretender. The Australian, Swiss and Canadian currencies although being considered as safe heavens by investors cannot take the number 1 spot because their economies are too small. There is also a willingness of foreign investors and countries like China for a viable alternative to the dollar.

Creating a Eurozone economic government, issuing Eurobonds, completing the banking union and expanding the ECBs mandate by adding financial supervision and unemployment are essential steps in the right direction. Europe, as the world’s largest economy has a duty in shaping and challenging the current international financial order to the interest of its citizens. Only by speaking and acting as one will it be successful in doing so.

John Connally, Richard Nixon’s Secretary of the Treasury, once told worried European finance ministers: “The dollar is our currency but your problem.”

Hamza Serry-Senhaji is a pan-European activist who is currently in JEF Brussels as the treasurer of the organisation. His monthly column, The Pan-European Pen, brings focus to topics that are crucial for a common European future.

Related articles